In a previous post, I wrote about the characteristics of truth. I described truth as statements that describe or concord with objective reality. These statements involve making a claim about a particular object or concept (e.g. there is water on Earth), and the truthfulness of the statement can often be tested by observing the object described. In this post, I’ll go into more detail on specific types of statements that are always true, no matter what kind of object, real or abstract, they are referring to.

Logical Formulas and Truth Tables

There are two different flavors of truth: Logic and Facts. A fact is simply an accurate description of anything, such as “there is water on Earth.” Logic, on the other hand, consists of conditional statements called “formulas,” involving placeholders for facts or other logical statements. The word “logic” can be ambiguous; sometimes it refers to the study of all such formulas, and other times it refers only to formulas that are objectively true in all cases, no matter which facts are inserted into the statement. Another word for a logical formula that is true in all cases is a “tautology.” Tautologies are useful because they can be applied to facts to generate more facts, and they can be applied to tautologies to generate more tautologies.

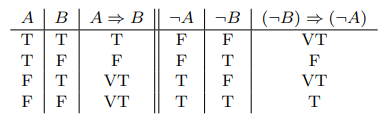

Logical statements or formulas are often written symbolically. For example, the statement, “if A then B” is written A⇒B. This formula can also be read as “A implies B,” or “B is true whenever A is true.” The truth of this statement depends on the identities of A and B. For example, in the case where A is true and B is true, then the statement might be true, but if A is true and B is false, then the statement must be false. The statement’s designation as true or false is called the “truth value” of the statement. It is common practice to build a “truth table” to evaluate possible truth values. An example of a truth table for the statement A⇒B is shown here:

In constructing the table, we run through every possible combination of truth values for the variables A and B. The first two rows of the table correspond to the examples we considered previously. If truth tables are new to you, then the last two rows may seem strange. In both the third and fourth rows, the “antecedent” A in the statement is false. One could argue that the statement A⇒B simply does not apply in this case, and yet it appears that we have assumed it to be true anyway. In these cases, the formula is said to be “vacuously true.” The vacuously true cases do not disprove the formula, but still, you may be wondering why we give it the benefit of the doubt? I will explain why this is the correct approach using three arguments.

First, the formula A⇒B does not imply any causal connection between A and B. It simply states that “B is true whenever A is true.” So the question we should be asking in each case is not “Is A causing B,” but rather, “Can we say that B is true whenever A is true?” If A is false, we can still say that B is true whenever A is true, so we can assign a truth value of T.

Second, consider another statement (A∧B)⇒B, which can be read “B is true whenever A and B are both true.” Without thinking about truth tables, it may be obvious to you that this formula is always true. If A and B are both true then of course B is true. But if we build a truth table for this formula, when we reach the case where A and B are both false, we run into the same dilemma as before. Can we still say that the formula holds in every case? Yes, we can, so we assign it a truth value of T. This argument is based on Robert Stoll’s Set Theory and Logic, page 165.

Third, consider the contrapositive statement (¬B)⇒(¬A), which can be read “Not B implies not A,” or “A is not true whenever B is not true.” It is clear that the contrapositive and the original statement, A⇒B, are logically equivalent. They are both saying the same thing. There is no additional information contained in one formula compared to the other. Yet if we build a truth table, we find that the vacuous truth values appear in different rows of the table. I have recreated the original truth table below with the vacuous truths explicitly denoted by VT, with the contrapositive table appended to the right-hand-side.

The original statement is vacuously true in the third and fourth rows, while the contrapositive is vacuously true in the first and third rows. Suppose that we had gone the route of saying that a statement simply doesn’t apply in the cases where it is vacuously true. Such an approach would tell us that the useful cases of the original statement and its logically-equivalent contrapositive are different, in blatant disagreement with our logical intuition. If we accept that the contrapositive is equivalent to the original statement, then we must conclude that vacuous truth is just as truthful and useful as non-vacuous truth. In short, vacuous truths are necessarily true to preserve the consistency of logical formulas.

From now on, I will treat vacuous truths no differently from non-vacuous truths. I do this not by convention or convenience, but because it is the correct approach.

Tautologies

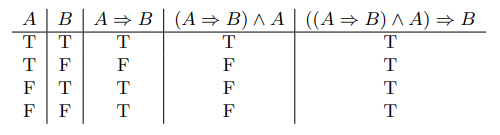

We will now proceed to analyze another more interesting formula: if A implies B, and A is true, then B is true. This is the syllogism, which is probably the most famous example of a tautology. Credit for its original formulation is usually given to Aristotle of Ancient Greece. If we run through the possible truth values of A and B and build a truth table, then we see that the syllogism is true in all cases.

The undeniable truth of the syllogism (or any tautology) makes it extremely useful in arguments. If the premises A⇒B and A are true, then the syllogism passes their truth value on to the statement B with absolute certainty. Here is an example:

A: A proton is made of quarks.

A⇒B: If a proton is made of quarks, then it is a hadron.

Applying the syllogism leads to the inevitable conclusion:

B: A proton is a hadron.

If we accept the premises, which in this case are an observation and a definition, then the syllogism forces us to accept the conclusion. We cannot deny the conclusion unless we can negate one of the premises that led to it.

Many other tautologies can be identified by constructing truth tables. One of the simplest is P⇒P. This statement appears redundant, but it is actually useful. If we replace P with “an organism tends to survive and reproduce,” then it becomes the foundation of the theory of natural selection of organisms: “If an organism tends to survive and reproduce, then it tends to survive and reproduce.”

Mathematics

The logical statements that we have considered so far all belong to the field of propositional logic, also known as zeroth-order logic. Although it is absolutely valid and very useful, it is limited in its scope. For example, consider the statement, “All sheep are white.” The negation of this statement in propositional logic is “Not all sheep are white.” Your intuition probably tells you that this negation can be further developed. By thinking in a higher order of logic, we can conclude that the negation is equivalent to “There exists at least one sheep that is not white.”

This last statement is an example of first-order logic. It is not a different kind of logic, with different rules about what is true and what isn’t, it is simply an extension, or further development of the foundational zeroth-order logic. As you might have guessed, the development of logic does not end at first-order. It can be extended to second-order logic and beyond. The higher orders of logic are the foundation of the field of mathematics.

Mathematics is the study of abstract structures and the logical relationships between them. It is as old as logic itself and actually consists of pure, undefiled logic. Every mathematical theorem is a conditional statement: “If these axioms and conditions hold and we accept the definitions then such and such is guaranteed.” These theorems are all proven rigorously so that we can know with absolute certainty that they are true, or at least that they are consistent with the accepted definitions and axioms. I have heard it said that every debate among mathematicians is a debate over definitions, because everything else follows logically and cannot be debated.

There is a great dilemma in the philosophy of mathematics regarding the validity of its foundational axioms. For those who are unfamiliar, an “axiom” is a statement that is evidently true but cannot be proven. For example, one of the most debated axioms in history was Euclid’s Fifth Postulate. It was an axiom of geometry presented in Euclid’s Elements, which simply implied that two parallel lines will never cross each other. Long thought to be obviously and inevitably true, Euclid’s Fifth Postulate turned out to be an assumption. Today, the most popular foundation for our current system of mathematics are the axioms of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory. Most of these axioms involve claiming the abstract existence of certain mathematical objects, and they seem to be obviously true to those who understand them. But is it possible that we are following the footsteps of the ancient greeks and making a naive assumption that limits the scope of our mathematical tools? Are we assuming something that is not necessarily true? Is all of mathematics based on a shaky foundation?

Not to worry. Even if it turns out that one or more of our axioms are not necessarily true, it will not negate the validity of our mathematics in the cases where they are true. Just as “Euclidean” geometry still exists and is very useful today, our mathematics will never be invalidated.

Conclusion

The purpose of this post is to clarify the rigorous foundations of logic and mathematics. Logical tautologies and mathematical theorems are examples of eternal, immutable truths. No power in heaven or earth can negate them. They are rules that transcend time, space, and all of physical existence. Any intelligent civilization that might come into existence would discover the same rules that we have discovered. This is part of what makes the study of mathematics so exhilarating.

In future posts, I will make use of tautologies and mathematics to prove certain statements. Rather than reinvent the wheel each time, I will likely reference this post to justify my use of these tools. While their reliability is unquestioned, their applicability must be demonstrated by showing that the properties of a system satisfy the premises of the tool I wish to use. That is where errors can enter in. Thus, the study of mathematics, like any other trade, involves learning what tools are available and when to use them, except the tools of mathematics are eternal, indestructible, and incorruptible.